Kidney Disease: A Price-Sensitive Market But A Bundle Of Opportunity

Executive Summary

Medicare’s bundling policy for drugs and services in dialysis has turned on the pricing pressure in kidney disease. The cost containment policies have negatively impacted sales of some drugs and put a spotlight on growing costs in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Nonetheless, there is plenty of opportunity for new drugs that can address the area’s unmet medical need, especially if they can help to reduce broader health care spending. That will require demonstrating value to payors and providers, however, particularly for drugs that treat secondary conditions associated with kidney disease.

- Medicare’s cost-containment policies to reduce drug spending in dialysis went into effect January 1, 2011, and hurt sales of some drugs used in the setting, notably erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Pricing pressure isn’t going to ease up, so drugmakers looking to bring new treatments to market will have to present a solid value story to payors and dialysis providers.

- Partners Abbott and Reata are poised to take advantage of the enormous market opportunity for a drug that addresses kidney function and could potentially delay progression to dialysis, but their ultimate success hinges on results of an ongoing Phase III outcomes trial.

- Affymax and Takeda are experiencing the effects of the reimbursement climate first-hand with the launch of the long-acting ESA Omontys. Despite a once-monthly dosing advantage over the current standard of care, the new drug is priced lower, part of an initiative to encourage dialysis providers to switch.

- Kidney disease may be the canary in the coal mine; companies who adapt to Medicare’s stricter bundling policies will be well-positioned to tackle reimbursement hurdles elsewhere, both from public and private payors.

Medicare’s “bundling” policy, intended to reduce drug spending in the dialysis setting, has turned pricing pressure into a choke hold in kidney disease. The cost containment policies for intravenous drugs went into effect Jan. 1, 2011, making the year a tense one for some drugmakers working in the therapeutic area. And the measures are set to extend to oral drugs in 2014, which means pricing pressure in dialysis isn’t going to diminish anytime soon.

But the number of patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease is growing, the unmet medical need is enormous, and costs are soaring. Patients and physicians are desperate for new treatments and payors – the biggest one of which is the US government – would roll out a red carpet for a new drug if it would help reduce health care spending. The most clear-cut opportunity in kidney disease is for a drug that would delay the progression of the disease, slowing patients’ progression to dialysis, a life-altering treatment for patients and a drain on the health care system.

But that golden nugget has been unattainable in drug development thus far. Most of the drugs used to treat patients with CKD lower cholesterol, blood pressure or blood sugar, which is to say they address the major contributors to the disease, but not the loss of kidney function itself. Other drugs, including erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, phosphate binders and calcimimetics are used for secondary conditions like anemia and bone disorders caused by kidney disease. Patients with CKD continue to progress through five stages of the disease, determined by kidney function and measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), until they either receive a kidney transplant or reach ESRD, when the kidneys fail and patients begin dialysis treatment. The paradigm has changed little in the last decade.

Partners Abbott Laboratories Inc. and Reata Pharmaceuticals Inc. are poised to shake up the treatment paradigm. The drugmakers are in the best position to capitalize on the lucrative market opportunity for delaying disease progression with the late-stage drug bardoxolone methyl, which could potentially be the first disease-modifying drug to delay progression or even reverse the course of the disease. But there are no guarantees in drug development and the bardoxolone story won’t necessarily have a happy ending until the results of an ongoing Phase III study read out.

More common in pharma’s R&D labs are drugs in mid- to late-stage development for secondary conditions caused by kidney disease like anemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT). In these areas, the key value drivers are harder to define and well-established competitors already dominate the market. New drugs with enhanced efficacy, safety or convenience may be welcomed by patients and physicians, but developing a clear value story for payors may prove more challenging. This market is further complicated in that in the later stages of disease, when patients reach dialysis, treatment decisions are often directed by dialysis providers, with an eye on overall health care costs, not individual physicians.

New drugs with enhanced efficacy, safety or convenience may be welcomed by patients and physicians, but developing a clear value story for payors may prove more challenging.

The lesson is one Affymax Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. are all too familiar with. The launch of their new long-acting ESA, Omontys (peginesatide), is an interesting case study for others in the industry. Though not their original intention, the companies are using the cost containment pressure in the dialysis space as leverage to gain a foot-hold in the market. They priced Omontys below the market leader, Amgen Inc.’s Epogen (epoetin alfa), despite Omontys’ dosing advantage, to give dialysis providers a compelling reason to switch. As Affymax CEO John Orwin explains it, “The less frequent dosing and whatever benefits attend to that are really icing on the cake. They’re important but they are not what we expect to drive the use of Omontys.”

The Cost Of Kidney Disease

Total Medicare expenses for patients with CKD were $34 billion in 2009, and $29 billion for patients with ESRD, according to the United States Renal Data System 2011 Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease. The USRDS is a national data system funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, which collaborates with CMS, the United Network for Organ Sharing and the ESRD networks on data sharing. In the US, 571,414 patients are under treatment for ESRD and some 30 million are believed to have CKD, though the disease often remains undetected in the early stages.

It’s not surprising then that CMS is looking for ways to reduce the cost of treating kidney disease, and given the high cost of dialysis, that setting has been a primary target. Delaying progression to dialysis or averting it altogether would represent an enormous quality of life benefit for patients and an equally substantial cost savings for payors. The cost of dialysis was $82,288 per patient per year for patients on Medicare in 2009, according to USRDS (an organ transplant costs Medicare $29,983 per patient).

To help lower costs, CMS implemented a new bundled payment system for drugs and services related to ESRD treatment under Medicare Part B. Under the new system, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2011, the costs of providing care to dialysis patients, including drugs, are reimbursed together in a single capitated rate, which removes the incentive for dialysis providers to over-prescribe certain drugs like ESAs or use pricier brands when cheaper alternatives are available. For example, in the case of IV iron, that means using older drugs like Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd.’s Luitpold Pharmaceuticals Inc.’ Venofer (iron sucrose) over AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc.’s newer and pricier Feraheme (ferumoxytol). (See (Also see "AMAG Pharmaceuticals: Enough Irons In The Fire?" - In Vivo, 1 May, 2010.).)

For now the bundle only includes intravenous drugs, like anemia agents, IV iron and IV vitamin D. That will change in 2014 when some oral drugs used in dialysis will be added to the bundle, a move that will have further implications on drugs like phosphate binders, vitamin D analogues and calcimimetics. (See (Also see "Delaying Inclusion Of Oral-Only ESRD Drugs In Bundled Payment Gives Short-Term Reprieve To Genzyme, Amgen" - Pink Sheet, 2 Aug, 2010.).)

The cost of ESAs per person per year for patients on dialysis was $6,175 in 2009, according to the USRDS. In addition to ESAs, which are reimbursed under Medicare Part B, the total cost of drugs reimbursed under Medicare Part D is also substantial, about $5,536 per patient per year for patients on dialysis, an amount that is 2.3 times higher than in the general Medicare population, according to USRDS. (See Exhibit 1.)

Exhibit 1

Top 25 Drugs Used By Medicare Part D-Enrolled Dialysis Patients By Net Cost, 2008

Generic Name | Total Days Supply | Total Cost in US Dollars |

Sevelamer HCI | 17,804,550 | 255,639,977 |

Cinacalcet | 12,051,8081 | 213,384,687 |

Calciumacetate | 13,198,502 | 49,785,847 |

Insulin | 15,630,838 | 49,270601 |

Lanthanumcarbonate | 3,001,874 | 48,825,125 |

Clopidogrel | 8,855,704 | 33,549,441 |

Atorvastatin | 7,398,132 | 21,884,604 |

Esomeprazole | 4,254,689 | 20,854,548 |

Amino acids 8% | 231,171 | 18,831,418 |

Pantoprazole | 5,442,180 | 17,187,145 |

Sevelamercarbonate | 992,319 | 14,049,386 |

Lansoprazole | 2,723,129 | 13,609,627 |

Nifedipine | 6,461,228 | 11,887,174 |

Pioglitazone | 2,332,897 | 11,483,495 |

Clonidine | 10,286,086 | 10,971,889 |

Valsartan | 4,377,843 | 10,503,139 |

Omeprazole | 7,875,290 | 8,586,724 |

Amlodipine | 15,120,000 | 8,129,829 |

Oxycodone | 1,140,867 | 8,008,673 |

Metroprotol | 18,519,761 | 7,879,893 |

Doxercalciferol | 724,126 | 7,467,454 |

Thalidomide | 42,735 | 7,191,397 |

Fluticasone/salmeterol | 1,221,841 | 7,182,088 |

Quetiapinefumarate | 1,017,911 | 5,872,095 |

Simvastatin | 10,151,596 | 5,794,211 |

United States Renal Network’s 2011 Atlas of CKD & ESRD

Abbott Revs Up Renal Engines

A company aiming to make a play in the kidney disease market needs to think big. Abbott, more than any other big pharma, is making a hard drive to address kidney disease in the earlier stages. The company is not new to the arena. It markets the vitamin D analogue Zemplar (paricalcitol) for SHPT, used mainly in dialysis patients. But the company is sharpening its focus to home in on pre-dialysis patients.

“What we really want to do is provide patients options to slow progression to renal failure,” says Abbott’s James Stolzenbach, PhD, divisional VP-dyslipidemia and renal. “We want to look at patients further upstream, patients that still have good renal function, where we can intervene medically to help them not have to go through a dialysis experience.”

“What we really want to do is provide patients options to slow progression to renal failure,” says Abbott’s James Stolzenbach, PhD, divisional VP-dyslipidemia and renal. “We want to look at patients further upstream, patients that still have good renal function, where we can intervene medically to help them not have to go through a dialysis experience.”

To that end, the company paid handsomely to buy ex-US rights (excluding some Asian territories) to bardoxolone methyl from Reata in September 2010. [See Deal] Abbott paid $450 million up front for rights to the first-in-class anti-oxidant inflammation modulator that activates the Nrf2 pathway, in an alliance that appears to include the highest upfront ever for a single Phase II asset. (See (Also see "Reata's $450 Million Up-Front Haul Sets A Record But Remains An Outlier" - In Vivo, 1 Oct, 2010.).)

The drug improved kidney function in patients with Stage IV CKD in a Phase II study called BEAM and could represent a significant advance in terms of slowing disease progression or even reversing the course of the disease. Given the potential size of that market opportunity, it’s no wonder Abbott is positioning bardoxolone as a future cornerstone of its new pharma spin-out AbbVie. “Bardoxolone could be a $1 billion-plus commercial opportunity for the Abbott territories alone,” EVP-corporate development Richard Ashley claimed during a conference call in October outlining the breakup of Abbott into a research-based pharmaceutical unit and a diversified health care company.

A drug that could keep patients from progressing to dialysis would challenge the recent pricing trends in kidney disease. But investors are anxious to see data from the Phase III BEACON study before popping the Veuve Clicquot. Unlike BEAM, which used improvement in eGFR as the primary endpoint, BEACON is an outcomes trial, with the primary endpoint being progression to dialysis, kidney transplant or death. The outcomes design was chosen to secure regulatory approval, but also with commercialization in mind, according to Reata CEO Warren Huff.

“The main value proposition is that bardoxolone prevents or delays progression to dialysis and death,” says Huff. “That data should directly inform patients, physicians and payors.”

Abbott’s Stolzenbach agrees. “What we really want to demonstrate is that we can slow that progression to renal failure,” he says. “If you haven’t done that you haven’t really got at the basic thing that drives the cost and burden of disease on the patient. It’s really the strongest way to demonstrate that bardoxolone is providing real benefit in patients.”

The event-driven trial is enrolling 16,000 patients and is expected to read out in 2013. Abbott and Reata, which has retained sole US marketing rights, have targeted 2014 for a launch. Abbott has been pleased with what it has seen so far. In December, the company expanded its partnership with Reata to develop and commercialize second-generation oral anti-oxidant inflammation modulators in various areas including pulmonary conditions, central nervous system disorders and immunology, handing over another astounding $400 million up front. [See Deal]

Abbott’s pipeline also includes atrasentan, an endothelin-A receptor antagonist developed in house and now in Phase IIb testing for diabetic kidney disease. Atrasentan, originally studied as a potential oncologic, blocks a protein that raises blood pressure and impacts kidney function. Abbott views atrasentan as a potential complementary drug to bardoxolone.

“For atrasentan, we are focused on patients that have diabetes with proteinuria and are looking at patients that are not quite as far progressed as the patients that are treated with bardoxolone in the BEACON study,” says Stolzenbach. “These are patients further upstream, so the two products fit very well into our paradigm of having multiple mechanisms of action and trying to attack the problem in various stages of renal function.” In May, Abbott also paid $110 million to Action Pharma AS to acquire the hormone analogue AP214 in Phase IIb development to prevent acute kidney injury associated with major cardiac surgery. [See Deal]

Anemia And SHPT Still Lure Drugmakers

Potential disease modifiers like bardoxolone are few and far between. Drugs that treat the various secondary conditions associated with CKD like anemia and SHPT, a condition that results in serious bone disorders, are more common. In these therapeutic areas, where first-generation drugs already have a solid foothold in the market, the competition is fierce and new products that come to market without a compelling pharmaco-economic story are likely to face backlash from payors. And since these drugs are typically added to the treatment armamentarium later in the course of the disease, when patients are on dialysis, they also come under the scrutiny of dialysis providers.

Experienced player Amgen is continuing to invest in kidney disease despite the challenging market dynamics. The big biotech is more familiar than most with the price sensitivity of the market. Epogen, the market-leading ESA in the dialysis setting, has taken the brunt of the hit from the implementation of Medicare’s new bundling rules last year, and was also impacted by FDA labeling changes to lower dosing due to ongoing safety concerns. Amgen also markets Aranesp (darbepoetin alfa) and manufactures Procrit (epoetin alfa), sold by Johnson & Johnson, but those ESAs are used more in the cancer setting and pre-dialysis setting, where they are also facing challenges due to safety issues with the entire class of drugs. (The market for anemia treatment in the pre-dialysis setting could potentially be significant, but ESA usage has been greatly restricted in the area due to concerns over the cardiovascular safety of the class.)

Amgen also markets the SHPT drug Sensipar (cinacalcet), which will come under pressure when oral drugs are added to the bundle in 2014. Sensipar is an important brand for Amgen, especially as sales of its blockbuster ESAs have faltered amid reimbursement and safety issues. Sensipar’s sales are continuing to grow; the drug generated $808 million in 2011, reflecting 13% growth, but that growth will be challenged in 2014.

“Cinacalcet is going to have a major problem unless Amgen cuts their price significantly,” speculates one nephrologist, Jay Wish, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. “It is way too expensive to be in the bundle.”

“Cinacalcet is going to have a major problem unless Amgen cuts their price significantly,” speculates one nephrologist, Jay Wish, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. “It is way too expensive to be in the bundle.”

Decision Resources, Inc.’s Sharon Funk, VP of market research services for BioTrends Research Group, agrees. “We have done a lot of research on bundling and physician perception when orals are included,” she says. “The expectation is that people are going to go for lower cost products.”

Complicating matters further for Sensipar, Amgen announced June 8 that a Phase III outcomes trial, studying the in patients with SHPT and chronic kidney disease receiving dialysis failed to meet the primary endpoint of demonstrating a statistically significant reduction in cardiovascular events compared to placebo. That won’t help Amgen’s case when it begins negotiating with dialysis providers ahead of the bundling implementation.

“Following bundling at the end of 2013, Sensipar use would likely decline as standard of care is significantly cheaper and demonstration of an actual reduction in CV outcomes with Sensipar remains elusive,” says Barclay’s Capital analyst C. Anthony Butler in a same-day research note. In addition, he says Sensipar’s failure in the EVOLVE trial calls into question Amgen’s acquisition of KAI Pharmaceuticals Inc. earlier this year.

Amgen announced an acquisition in April, buying potential competitor KAI Pharmaceuticals Inc. for $315 million. [See Deal] The acquisition gives Amgen KAI-4169, a peptide agonist of the calcium sensing receptor in Phase IIb for the treatment of SHPT in patients with CKD who are on dialysis. (See (Also see "Amgen Planned Acquisition Of KAI Would Bring In Replacement For Sensipar" - Pink Sheet, 10 Apr, 2012.).) KAI-4169 is being developed as an IV formulation that could be administered in conjunction with dialysis. That could make a more compelling value case for dialysis providers who could administer the drug concurrent with dialysis treatment and be assured patients are taking the product and receiving the benefits they are paying for. Sensipar, sold as tablets, is associated with a high pill burden, adverse events like nausea and vomiting, and poor compliance rates. In fact, the majority of patients don’t remain on therapy after 12 months.

But Barclay’s Butler says, “We believe that the failure of Sensipar to show an outcomes benefit over existing standards of care (vitamin D analogues and phosphate binders) would be a barrier to uptake [of KAI-4269].”

Plus, Sensipar is set to go off patent in 2018, and the availability of low-cost generics would surely test the marketing savvy of Amgen with ’4169. In addition, patent protection for Sanofi’s phosphate binder Renvela (sevelamer) expires in 2014 and several patent challenges are underway, and protection for Abbott’s Zemplar expires in 2016. The availability of low-cost generic versions of Renvela or Zemplar will further encourage use of those drugs over Sensipar.

In anemia, the biggest potential new change could be the introduction of oral hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors, several of which are in development and work through a different mechanism of action than ESAs. Anemia candidates from Akebia Therapeutics Inc. and FibroGen Inc. have both completed Phase II testing. The drugs have not demonstrated the cardiovascular safety issues linked to ESAs, which are known to increase hypertension in CKD patients. In fact, in a Phase II study testing FibroGen’s FG-4592, the drug reduced blood pressure in hypertensive patients and reduced cholesterol levels. Better safety and potential efficacy benefits on known contributors to kidney disease could position HIF inhibitors for far broader use, including in the pre-dialysis setting.

FibroGen believes there are more than one million anemic CKD patients in the US, and that less than 22% are being treated with ESAs prior to initiation of dialysis. The value proposition for FG-4592 is clear, CEO Thomas Neff says. An efficacious oral pill with a demonstrated cardiovascular safety profile that has also shown benefits on hypertension and cholesterol and for which no IV iron supplementation is required offers multiple therapeutic benefits and cost benefits as well, he says. Plus, “We are not going to seek a giant premium,” Neff says. “We think access makes sense.”

FG-4592 is partnered with Astellas Pharma Inc. in Europe, the Middle East, South Africa and Japan, [See Deal] but remains un-partnered in North America. FibroGen is weighing its North American partnering options and is planning to initiate several Phase III studies later this year testing FG-4592 in the dialysis and pre-dialysis settings. “We could detail to a single market like endocrinology or nephrology alone, but if we are going after several different markets at once we are going to need someone with horsepower,” Neff adds.

Akebia’s drug, AKB6548, is un-partnered and the company is also evaluating options. “We do have a lot of pharmaceutical interest right now,” says CEO Joseph Gardner. (See (Also see "P&G Spinout Spins Off Another Company, While Looking To Partner Mid-Stage Oral Anemia Candidate" - Pink Sheet, 21 May, 2012.).) “For a large disease indication like anemia, where you have to run a Phase III program that involves a non-inferiority analysis on a fairly large database, that is a fairly expensive Phase III program. The question is do we try to fund that ourselves or try to get a pharma to fund it? I think both are very possible and both are being explored.”

ESAs Under Fire

For now the heat is squarely on ESAs, a market that has been thrown into an upheaval due to Medicare’s reimbursement policies, cardiovascular safety issues and the launch of the first long-acting ESA to hit the US market.

ESAs are the most expensive part of the bundle and as a result, have been affected the most. Of the $2.78 billion spent in 2009 on injectable drugs in the dialysis setting, ESAs accounted for 68% or $1.89 billion, according to the 2011 USRD Atlas. In contrast, use of IV vitamin D, IV iron and other IV drugs accounted for 18.3%, 10.3% and 3.6% of costs, respectively.

The rationale for reducing use of ESAs is not only financial but also overuse. High doses of the medications have been linked to increased risk of death, serious cardiovascular reactions and strokes, which opened the door for lower prescribing on a medical basis. FDA in June 2011 updated labeling for ESAs in the renal setting to highlight the risks of administering ESAs to a target hemoglobin level of greater than 11 g/dL and to remove the floor. Labeling previously recommended ESA dosing to achieve hemoglobin levels within the range of 10 g/dL to 12 g/dL and pointed to the risks associated with ESAs when administered above 13 g/dL. CMS followed by similarly lowering the target upper level to 11 g/dL and retiring the floor hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL in its prospective payment system. (See (Also see "Medicare Proposes Changes To Target Hemoglobin Levels In ESRD Treatment" - Pink Sheet, 11 Jul, 2011.).)

The result leaves physicians walking a tightrope, reducing use of ESAs to the lowest possible extent before patients require blood transfusions, a procedure that carries its own risks and cost burden. Physicians are using a number of strategies to balance appropriate use and cost, including increased use of iron to treat anemia in place of ESAs or even subcutaneous administration of ESAs in place of IV, though patient preference tends toward IV.

“People are still looking for ways to save on ESAs because it is the biggest-ticket item under the bundle,” says Case Western Reserve’s Wish. “If there is any other way you can [treat anemia] in terms of better iron use or more consistent application of ESA dose titration protocols or giving it subcutaneously, then all of those things are fair game.”

Fresenius SE & Co. KGAA’s Fresenius Medical Care AG, the largest dialysis provider in the US, took a proactive approach ahead of the bundling implementation to develop standardized treatment programs. The organization ran a series of six head-to-head trials starting in mid-2010 to narrow down the best protocols for ESA and iron utilization. It then implemented the protocol-based approach across its centers rather than allowing ad hoc prescribing, ahead of the reimbursement changes. The organization was forced to modify its protocols again in 2011 when FDA changed the ESA labeling. The result is that the average hemoglobin levels among patients on dialysis at Fresenius’ centers have fallen from a range of 11.4 g/dL to 11.5 d/gL to just below 11, says Chief Medical Officer Franklin Maddux, MD. The number of patients whose levels have fallen below 10 g/dL has increased slightly, he added.

“We have gotten more selective in making sure patients are achieving a competent iron position before receiving ESA,” he said. Fresenius runs 2,050 dialysis centers in the US, overseeing 150,000 patients in its outpatient chronic clinics. Fresenius represents about 38% of the dialysis market. The country’s other large dialysis provider is Denver-based DaVita Inc. Together, Fresenius and DaVita control two-thirds of the US dialysis market.

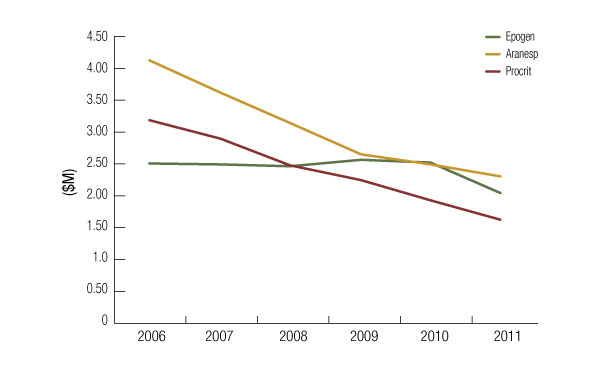

The safety review of ESAs has taken place several years, initially in the oncology setting. Thus, unlike Aranesp and Procrit, Epogen has largely been able to maintain steady sales since 2006, when concerns about cardiovascular issues initially emerged. The brand finally took a substantial hit in 2011 when the reimbursement rules went into effect and labeling was updated. (See Exhibit 2.) Worldwide Epogen sales dropped 17% year-over-year in the first quarter of 2012 to $446 million. Last year, sales of Epogen fell 19% year-on-year to $2.04 billion.

Exhibit 2

ESA Sales Slide

Since 2006, Sales Of The Leading ESAs Have Declined Due To Emerging Safety And Labeling Changes

Company reports

Aware of the safety concerns and reimbursement climate, investors at Amgen were anticipating the blow, but the question now is if the market has stabilized or if more changes are ahead. During a first quarter sales and earnings call, management at Amgen speculated that the ESA market is leveling off.

“This is a business in transition, and predicting usage over the past 18 months has proved difficult,” Executive VP-Global Commercial Operations Anthony Hooper said, referring to Epogen. “We do believe, however, that any further significant declines in hemoglobin levels would meaningfully increase the need for patient transfusions.”

“This is a business in transition, and predicting usage over the past 18 months has proved difficult,” Executive VP-Global Commercial Operations Anthony Hooper said, referring to Epogen. “We do believe, however, that any further significant declines in hemoglobin levels would meaningfully increase the need for patient transfusions.”

Indeed, there does appear to be mounting evidence that blood transfusions are on the rise – and that could give the medical community and policy makers pause. A new report from USRDS contributes to concerns that decreasing use of ESAs in dialysis patients can lead to a significant increase in the need for blood transfusions. Funded by National Institutes of Health (part of the US Department of Health and Human Services) and designed to track the impact of Medicare’s bundling rules, the study was presented to the National Kidney Foundation at a meeting in Washington, DC May 11. Using Medicare claims data through the first nine months of 2011, the study found that transfusions were up nearly 21% in September 2011 versus September 2010, USRDS Coordinating Center Director Allan Collins explains. By comparison, transfusions increased less than 3% from September 2009 to September 2010. The increase in transfusions came as the average dose of ESAs administered per person per month decreased 18.5% in the first nine months of 2011 versus the same period in 2010, he said.

Although the results are preliminary, regulators will be watching closely to see whether the Medicare bundling policy has a negative impact on dialysis patients. Transfusions can be risky and may compromise chances for a successful kidney transplant, if needed. An increase in transfusions could also substantially increase Medicare expenditures on hospitalizations.

In a prepared statement responding to the study, Patrick Conway, CMS chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality, said, “Medicare’s current payment policy for ESRD drugs is based on the latest evidence, reviewed by the FDA and CMS, about the safest and most effective treatment, and is designed to allow doctors and patients to make a decision about what treatment is best for each individual.”

Omontys: A Test Case

Affymax/Takeda’s Omontys is testing the tumultuous reimbursement waters, and easing in slowly. Though Omontys is the first long-acting ESA to hit the US market, the companies have made cost a cornerstone of the drug’s value proposition, demonstrating how significant an influence Medicare’s new policies are having. The companies launched the drug for the treatment of anemia in patients with kidney disease on dialysis in April with a once-monthly dosing advantage over Amgen’s Epogen, which is dosed 13 times per month. The long-acting ESA was approved by FDA March 27 to treat anemia in the dialysis setting, backed by clinical trial data demonstrating non-inferiority to Epogen when dosed monthly. (See (Also see "Affymax Anticipates Broad Opportunity For Omontys With Both Small And Large Dialysis Providers" - Pink Sheet, 2 Apr, 2012.).)

But the companies are largely relying on price to influence uptake. “The whole dynamic of a fixed-reimbursement creates a strong incentive for customers to want an alternative to their current ESA source,” Affymax’s Orwin explains. How successful Affymax and Takeda will be at selling Omontys to dialysis centers remains to be seen, but the pricing strategy could help the drug’s chances of success.

Launching Omontys into such a cost constrained and safety-focused market is far from what Affymax envisioned when it originally began studying Omontys in the clinic in 2004, and when Takeda signed on as a development and commercial partner in 2006. Then, the partners envisioned a $13 billion worldwide market opportunity that included the anemia market not only in dialysis, but in the pre-dialysis and cancer settings as well, where once-monthly dosing would have offered a greater convenience benefit. Patients on dialysis already visit medical centers several times a week for treatment, which limits the dosing advantage of Omontys in that setting.

In 2006, before the safety issues first arose with ESAs, sales of Epogen were $2.5 billion and sales of Aranesp were $4.1 billion. But Affymax ultimately chose not to seek approval for peginesatide in the CKD setting for patients not on dialysis or chemotherapy-induced anemia; a cardiovascular safety signal was seen in two trials comparing the drug to Aranesp. (See (Also see "Affymax's Peginesatide May Be Tough Sell To ODAC As ESAs Cast Long Showdow" - Pink Sheet, 5 Dec, 2011.).)

Under the 2006 deal, the Japanese pharma paid Affymax $105 million upfront in exchange for worldwide rights to market Omontys. [See Deal] The companies have a co-promotion and 50/50 profit-sharing relationship in the US, where Affymax is providing the sales force and Takeda the reimbursement and pricing expertise. Takeda also agreed to pay $280 million in development and regulatory milestones, and sales milestones of up to $150 million. Takeda has also submitted a regulatory application in the European Union.

But given that Omontys is launching into the dialysis market, where its dosing advantage is diminished, Affymax views the reimbursement environment as leverage. The company bets that dialysis providers will be swayed to switch from Epogen to Omontys if they can save money in the process.

The wholesale acquisition cost of Omontys is $108.10 per milligram, a price that puts Omontys dosed once-monthly on par with Epogen dosed 13 times a month, Affymax adds. The annual cost of treatment with Epogen is believed to be around $5,000 to $6,000 a year, according to Affymax, but cost varies by individual customer based on contracting through group purchasing organizations that include discounts and rebates. Amgen declined to provide pricing for Epogen. Including discounts and rebates, Affymax is looking to price Omontys below Epogen. Pricing ultimately will come down to contracting.

“The net effect of all of this, the wholesale acquisition cost, the off-invoice discounts, the performance-based rebates, is to ensure that the vast majority of customers will be able to treat patients with Omontys at a lower cost than what those same patients could be treated with with Epogen,” says Orwin. And the once-monthly dosing could still offer potential advantages in dialysis on secondary costs like nursing and administrative time.

Nonetheless, some still question how the safety and efficacy of a long-acting ESA will play out in the real-world setting, particularly when stacked up against the long track record of Epogen. Dialysis providers will have to weigh any benefits of Omontys against the complexity of shifting large groups of patients with sensitive hemoglobin targets to a new ESA. Indeed, Amgen warned, “Changing to a new product whose experience is limited to the clinical trial setting for the treatment of anemia for patients with CKD on dialysis should be considered very carefully.”

Complicating matters further for Affymax, Amgen signed new contracts with DaVita and Fresenius before Omontys launched, a seven-year exclusive contract with DaVita and a three-year non-exclusive one with Fresenius that blocks Omontys from having access to the majority of its patients.

Anxious For Alternatives

Still, dialysis providers and nephrologists are eager to have competition on the market. Fresenius plans to explore the use of Omontys further in a pilot study and then will consider adopting it more broadly. “Omontys presents something that has to be considered as an alternative,” Fresenius’ Maddux says. The company’s contract with Amgen allows for some use of other ESAs and it is in discussions with Affymax/Takeda on moving forward with a pilot program.

“If we determine that in fact this is a drug that has a role in the marketplace for physicians to use as an option to the drug we have all become very comfortable with and have used successfully for many years, then we would be addressing secondarily what is the most efficient use of ESAs,” Maddux says. “That is where you get into timing, cost, productivity of staff, consistency of dosing and all of those issues.”

Affymax and Takeda have accepted that Omontys will likely face a long-term launch trajectory; the expectation is that many dialysis centers will want to run pilots initially to gain experience converting patients from Epogen to Omontys. Nonetheless, the companies will need to establish Omontys’ position in the market in the next two years, before the drug faces competition from another long-acting ESA. Roche will be able to launch its pegylated erythropoietin product Mircera in the US in mid-2014. The company had sought to launch Mircera much earlier, in 2008, but was blocked by a patent infringement suit brought by Amgen. Ultimately the two companies settled, with Amgen agreeing to let Roche launch Mircera 10 months before the patents expire on Epogen and Aranesp. (See (Also see "Patent Power: Roche Concedes Case Over Amgen's EPO" - Pink Sheet, 22 Dec, 2009.).)

In the field of kidney disease, excitement – and the most lucrative dealmaking – will center around drugs that target patients further upstream. That is where drugs have the best chance to affect the course of the disease, generating significant sales for drug makers in the process – and saving payors money.

When those patents do expire in 2015, the market could become even more crowded, with the potential launch of biosimilar versions of Epogen. Biosimilar versions of the drug are already sold in Europe. In January, Hospira Inc. announced it had initiated a Phase III clinical program for its biosimilar version of Epogen. The study will enroll 1,000 patients on dialysis, with data expected in 2013. If and when biosimilars reach the market, the issue of cost will become that much more important.

The challenges facing drugmakers in kidney disease are not so different from those facing the broader industry. Mature drug markets are increasingly constrained, with experienced players feeling pinched and new entrants stepping into an opportunity that is more niche than once expected. But given the limited drug interventions in kidney disease and the fact that most patients progress to their deaths, a very real opportunity remains, more so than in most traditional primary care markets. And the cost savings from delaying progression to dialysis is a tangible value benefit. There is a takeaway for drugmakers across the industry as well. Pharmaceutical manufacturers that can accept that the reimbursement bar has been set a notch higher and adapt by addressing the unmet needs of both patients and payors are the ones that stand to succeed.

In the field of kidney disease, excitement – and the most lucrative dealmaking – will center around drugs that target patients further upstream. That is where drugs have the best chance to affect the course of the disease, generating significant sales for drug makers in the process – and saving payors money.