Is Pharma Doing Enough To Enable Access To COVID-19 Vaccines Everywhere?

Vaccine Efforts Falling Short In Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Executive Summary

The race to develop COVID-19 vaccines is intensifying long-standing debate over the ability of lower-income countries to gain affordable access to needed medical treatments. Patient advocates argue that drug makers and wealthy governments are striking deals that place poor countries at a disadvantage. The pharmaceutical industry, however, maintains it is moving as quickly as possible to not only discover safe and effective vaccines, but to enable equitable distribution.

In January, as a growing number of countries complained they were not receiving nearly as many COVID-19 vaccine doses as expected, Pfizer Inc. chief executive officer Albert Bourla announced that the drug maker and its partner, BioNTech SE, had agreed to supply up to 40 million doses to COVAX, the World Health Organisation program designed to ensure access to dozens of low and middle-income countries.

“This is one step in our long-term commitment to supporting developing countries and strengthen the global health care infrastructure,” Bourla explained, adding that the advance purchase agreement called for supplying COVAX at a “not-for-profit” price. He also described the deal as an initial agreement, suggesting additional doses could be provided through COVAX in the future.

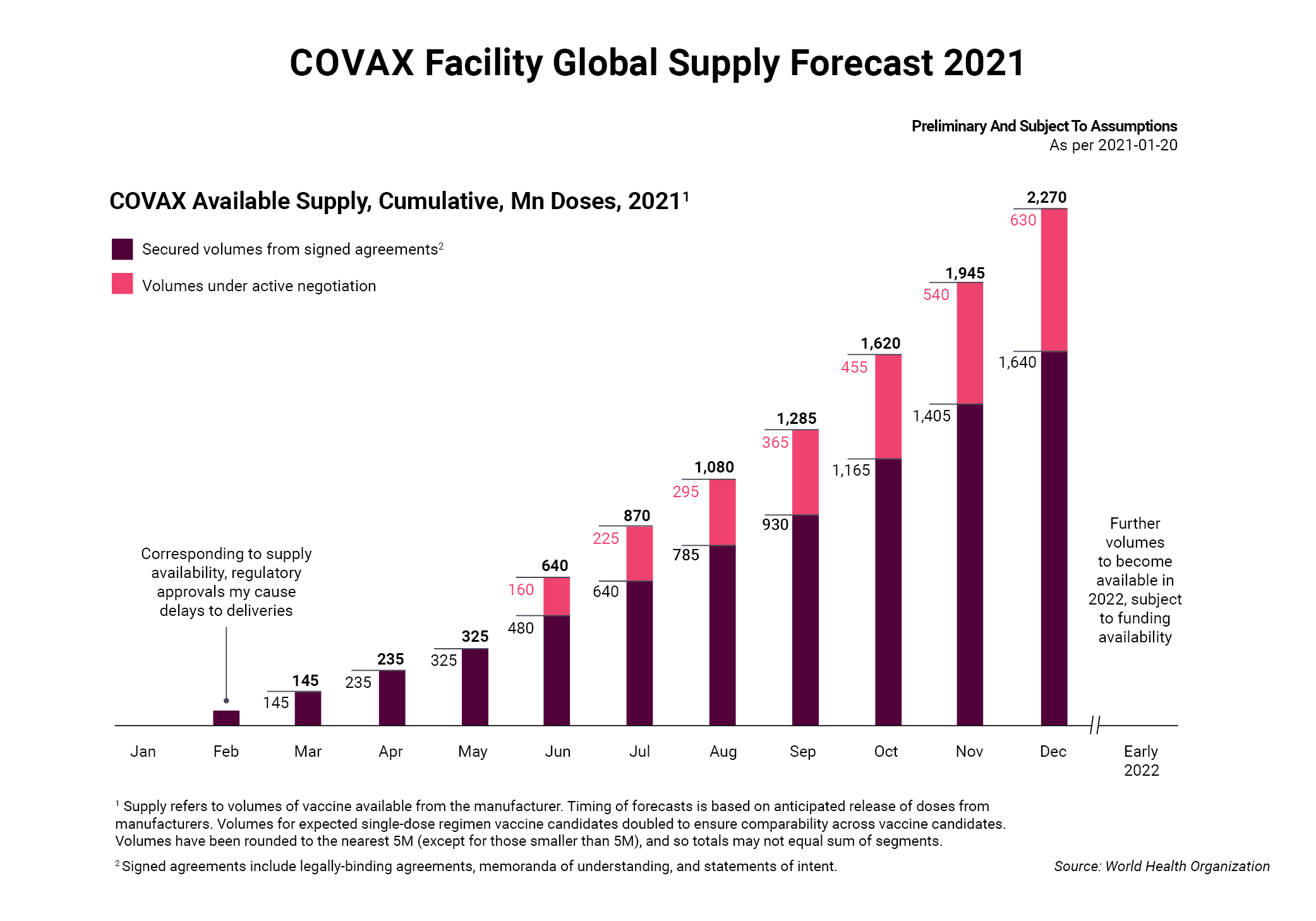

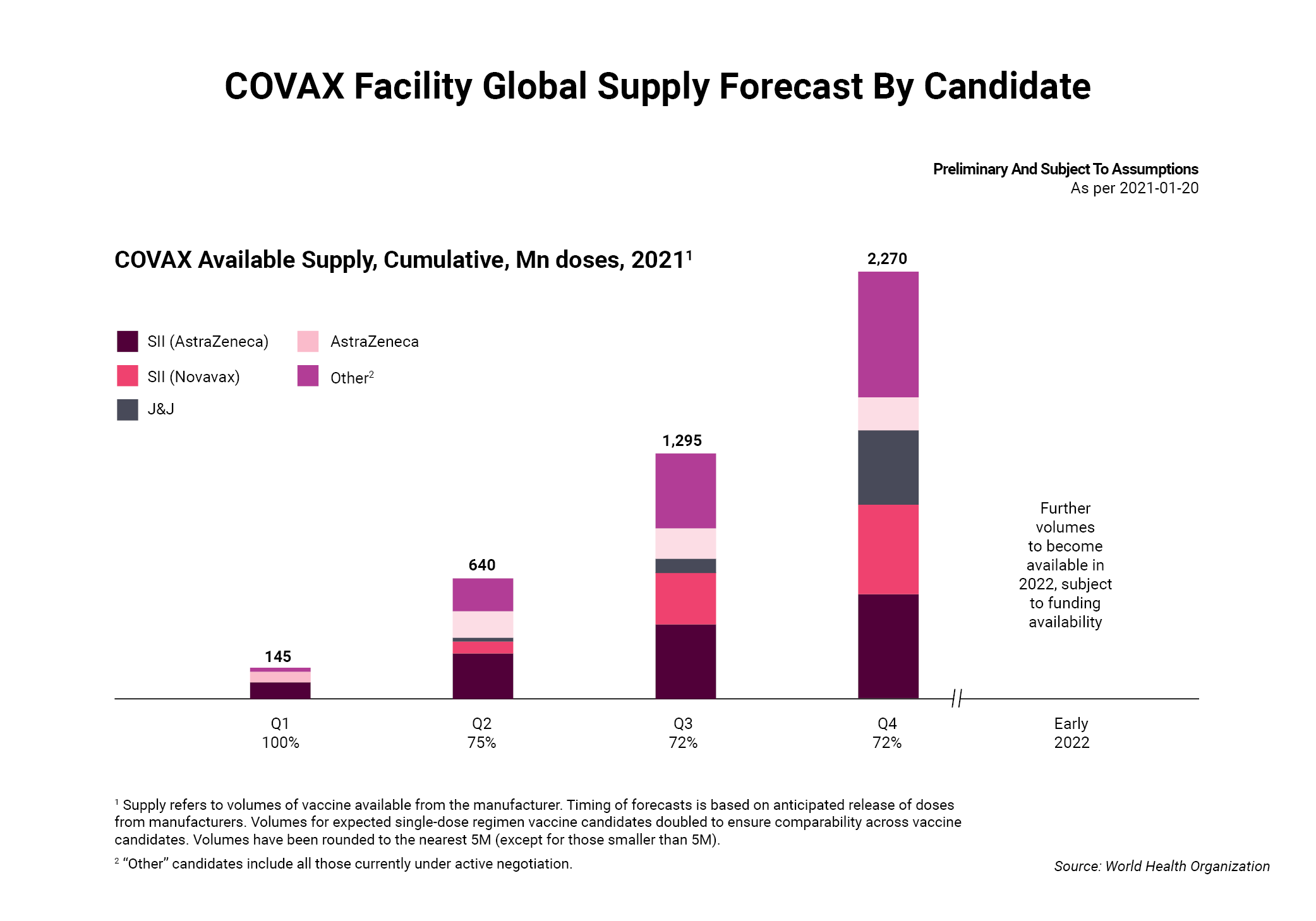

The commitment was praised by Seth Berkley, who heads GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, one of two nonprofits working with the WHO to administer the program. The Pfizer deal, he noted during a virtual conference call, moves COVAX closer to obtaining at least 2 billion vaccine doses this year and its goal of supplying 1.3 billion doses to 92 lower-income countries. If achieved, this could protect 20% of the population in each of the 190 countries that signed up to participate in the program.

The move followed months of work to attract donors and drug makers. For WHO director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Pfizer deal was an opportunity to express optimism about solving a momentous problem. At a WHO executive board meeting in January, he noted that 79 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in at least 49 higher income countries, while just 25 doses were given in one low-income country.

Although the deal clearly represented progress, reaction was decidedly mixed among advocacy groups that are pushing the pharmaceutical industry to accelerate their efforts to ensure poor countries have affordable access to vaccines sooner than later. In their view, the commitment that Pfizer made to COVAX was a step in the right direction, but still fell short.

Doctors Without Borders, for instance, noted that high-income countries have reached deals to buy 75% of the 2 billion doses to be manufactured by Pfizer this year. And of the 27.2 million doses delivered by the company as of mid-January, the nonprofit calculated that 99% went to high-income nations and about 250,000 doses went to middle-income countries. Low-income economies, so far, had not received any Pfizer vaccines.

“The deal is only 2% of their estimated total doses, a pittance considering their production capacity and the bilateral deals they’ve already struck with high-income countries. If Pfizer is serious about equity and supporting [COVAX], the bulk of its supply should be offered to COVAX and priced at cost,” said Dana Gill, US policy advisor for the group’s access campaign. As Pfizer has not disclosed costs, the group argues the not-for-profit price is hard to verify. AstraZeneca PLC, for instance, maintained it would not profit from its own vaccine until the pandemic is officially declared over, although under its contract with the European Union, the 27-member bloc agreed to pay about $400m to cover upfront costs and undisclosed amount for production.

Tension Over Access To Vaccines

For years, the notion of affordable access generally played out on a country-by-country, product-by-product basis, sparking what amounted to a fraught game of whack-a-mole between companies, governments and patient activists. Now and then, a government official would threaten to issue a compulsory license, which meant patents would be sidestepped, a tactic that drug makers decry as robbing them of monies needed to remain innovative.

In some ways, the largest drug makers have responded to criticism with useful steps, such as developing plans to ensure R&D projects are positioned to increase access in low-income countries after product launches, according to the Access to Medicines Foundation, a nonprofit that regularly examines industry efforts. Nonetheless, overall progress is still slow when it comes to improving access to lower-income economies, which the foundation described as “consistently overlooked” in its latest annual report.

Now, though, the dire situation created by the pandemic has ratcheted up scrutiny of the pharmaceutical industry, as well as wealthier governments with the means to not only pay huge sums for vaccines and therapies, but also help fund development.

“A year ago, when it became apparent that the new coronavirus outbreak was rapidly spiraling into a full-blown global pandemic, there was an expectation that this global crisis, as unfortunate as it is, would also bring the world together,” said Ellen ‘t Hoen, a researcher at the University of Groningen in The Netherlands, and former executive director of the Medicines Patent Pool, a United Nations-backed nonprofit that serves as a broker between governments and drug makers.

“There was an expectation that there would be greater collaboration in the development and production of new vaccines and treatments, and that the distribution would take place in a spirit of solidarity and equity. Barely a year later, reality turned out to be quite different … The global COVID-19 health crisis has so far not brought out the best in the international community and businesses. Instead, it is business as usual and poor people will bear the brunt,” she said.

A key problem is ‘vaccine nationalism,’ a term that popped up last year as wealthy nations began striking deals with different drug makers to lock in supplies, bypassing COVAX in the process. As recently as December, low- to middle-income countries, such as Brazil and Indonesia, had reserved less than one course for every two people, compared with wealthy nations that had reserved at least one vaccine course per person, according to an analysis in The BMJ.

Under the former Trump administration, for instance, production and developments deals worth roughly $12bn were reached. For instance, the US agreed to pay Moderna as much as $4.1bnfor at least 200 million vaccine doses and an option to buy 400 million more. A $2bn agreement was reached with Pfizer and Biotech for 100 million doses, while a $1bn deal was signed with Johnson & Johnson for up to 100 million doses by the end of June.

For its part, the European Union has spent about $3bn on down payments to secure nearly 2.3 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines from six different companies; separately, the UK has secured access to around 370 million vaccine doses from seven developers. Production constraints, however, have slowed deliveries, creating a furious row between EU officials and AstraZeneca. The issue is likely to continue until other drug makers win regulatory authorization for their shots or the production slack is eased through collaborations with other companies that have excess manufacturing capacity.

In any event, the US and EU have so far accounted for the vast majority of doses that have been contracted under advance market commitments, according to the Duke University Global Health Innovation Center. As of mid-January, the US reached agreements for as many as 2.6 billion confirmed and potential doses, and the EU was close behind. With commitments for 2 million doses, COVAX was on their heels, but there is no assurance the program can raise $4.6bn this year to secure supplies.

Unfortunately for everyone, successfully supplying COVID-19 vaccines is a fast-moving target shaped by a variety of factors. These include production capabilities, a growing number of variants of the virus that may require booster shots, and the ability of still other manufacturers to successfully develop safe and effective vaccines and therapies. Underscoring the precariousness of it all, Merck & Co. recently discontinued two potential COVID-19 vaccines, and a partnership between Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline has run into delays. “For COVAX to achieve its goals it needs to acquire the doses that have been committed to it by various vaccine producers, to then distribute these to countries that are depending on it,” said Kenneth Shadlen, a professor of international development at the London School of Economics, who studies pharmaceutical pricing, patents and access issues. “Whether – and at what pace – COVAX is able to do so depends on vaccines that are still in trials proving to be successful, the production schedules for approved vaccines, and how much of the output of each approved vaccine is also committed to individual countries. There are uncertainties in terms of the science and production, and there are unknowns in terms of the nature of the contracts that pharmaceutical firms have reached with COVAX and other purchasers.”

Are Wealthy Nations Missing The Point?

Indeed, one sticking point has been a lack of transparency over agreements, spawning debate over the prices different countries are paying, the extent to which taxpayers are funding development and production, and whether supply obligations are being fulfilled. This last point was at the heart of the row between AstraZeneca and the EU. Criticism has also been aimed at the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, or CEPI, which is working with GAVI and the WHO to administer COVAX.

“Transparency is important for many reasons,” said Jamie Love, who heads Knowledge Ecology International, an advocacy group that examines intellectual property rights to advocate for greater access to medicines. “One is to find out what rights the government has, or does not have, and to make policy makers accountable for what they negotiated, and what clauses in the contracts they are willing or unwilling to use.”

Yet wealthy nations should want to make certain that poor countries are equally able to access vaccines. The global economy stands to lose as much as $9.2tn if governments fail to ensure developing economies have access to COVID-19 vaccines, and up to half would fall on advanced economies, according to a study from the International Chamber of Commerce Research Foundation. For this reason, wealthy countries should want to invest in the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, the WHO program to accelerate development, production, and access to tests, treatments and vaccines.

For individual countries, the numbers are sobering. If advanced economies continue to prioritize vaccination of their susceptible populations without ensuring equitable vaccination for developing economies, the study estimated the economic cost to the US would be anywhere from $45bn to $1.38tn. For the United Kingdom, the cost would range from $8.5bn to $146bn, and for Germany, the tab could be anywhere from $14bnto $248bn.

Such projections are not hard to imagine, given that the global economy is increasingly interconnected. Countless supply chains that rely on less-developed countries for a wide array of goods are vulnerable if COVID-19 continues to hobble those economies. But a growing coterie of advocacy groups are convinced that wealthy nations are missing the point, because there is continued resistance to support the idea of openly sharing intellectual property and other know how to produce COVID-19 medical products.

One example is the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, or C-TAP, which was launched last spring by the WHO in hopes of persuading drug makers and other companies to share their knowledge and technology. The goal is to lower production costs and ease global shortages of needed drugs. Yet the effort has failed to get off the ground, largely because the pharmaceutical industry is concerned about relinquishing rights to patents. So far, C-TAP has not attracted any contributions.

“There is nobody supporting the idea of sharing. Instead, it’s all about protecting the monopoly of pharmaceutical companies, which want to control supply and price,” said Mohga Kamal-Yanni, a global health and access to medicines consultant, who is advising the People’s Vaccine Alliance, a coalition that argues patents are an impediment to wider access. Among its members are Oxfam, Amnesty International and Global Justice Now.

The ideological battle is playing out at the World Trade Organization, where the South African and Indian governments have proposed temporarily waiving some provisions in a trade agreement governing intellectual property rights, which would make COVID-19 medical products more easily accessible, especially by low-income countries.

In arguing their case, South African and Indian officials maintain that the case-by-case or product-by-product approach required when individual countries attempt to use flexibilities provided in the existing trade agreement could be limiting during the pandemic. Nonetheless, the proposal has met with repeated resistance from wealthy nations, notably the US.

The IP Balancing Act

Several of these countries have been reiterating long-standing arguments that patent rights do not create barriers to wider access and affordability. The US, for instance, suggested a more targeted approach in which a license could be granted to a generic manufacturer to make a specific product for distribution in certain countries.

One example cited is Gilead Sciences, Inc., which reached such agreements last year with several generic makers for its remdesivir treatment. In a similar type of move, AstraZeneca, which developed its vaccine with Oxford University, agreed to share its technology with the Serum Institute of India, the largest vaccine maker in the country so that distribution could be accelerated. And Moderna, Inc. decided not to enforce its patent rights related to its vaccine and will also license its intellectual property to any COVID-19 vaccines to others after the pandemic has ended, although consumer groups contended the company should dedicate its technology to the WHO.

Such steps underscore a willingness by drug makers to step up, according to Thomas Cueni, the director general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers. In his view, the industry is adapting to extraordinary circumstance as quickly as possible while trying to acknowledge concerns about widening access.

“There is a legitimate expectation from global society that industry will make a best effort to facilitate global access … But how would you expect a company to engage later if they are told now there is a pandemic and we’ll take your IP rights away? -Thomas Cueni

“Our industry depends on intellectual property and we wouldn’t be without strong innovation,” Cueni said. “There is a legitimate expectation from global society that industry will make a best effort to facilitate global access … But how would you expect a company to engage later if they are told now there is a pandemic and we’ll take your IP rights away? That’s why the WTO waiver hasn’t gotten much traction. You wouldn’t have a single dose more if you suspend patent rights.”

So far, though, most companies have not appeared all that eager to pursue licensing. Last November, the Medicines Patent Pool announced that 18 big generic drug makers had pledged to accelerate access to COVID-19 treatments for low- and middle-income countries. The idea is to encourage brand-name drug makers to negotiate deals to either license rights to their medicines or, where licenses are unnecessary, make it possible to increase manufacturing capacity. But no deals have been announced.

Meanwhile, the WHO director general tweeted a dire warning: “Until we end the COVID-19 pandemic everywhere, we won’t end it anywhere. As we speak, rich countries are rolling out vaccines, while the world’s least-developed countries watch and wait. Every day that passes, the divide grows larger between the have and have nots.”